Sequences of Assemblies

Sequences of stimuli

Many types of stimuli the brain encounters possess temporal structure, or sequentiality. Navigation involves a sequence of landmarks, planning consists of generating a sequence of actions, and language is nothing but sequences of tokens. If assemblies are the most basic unit of cognition, then sequences should be a natural higher-level structure to combine them into.

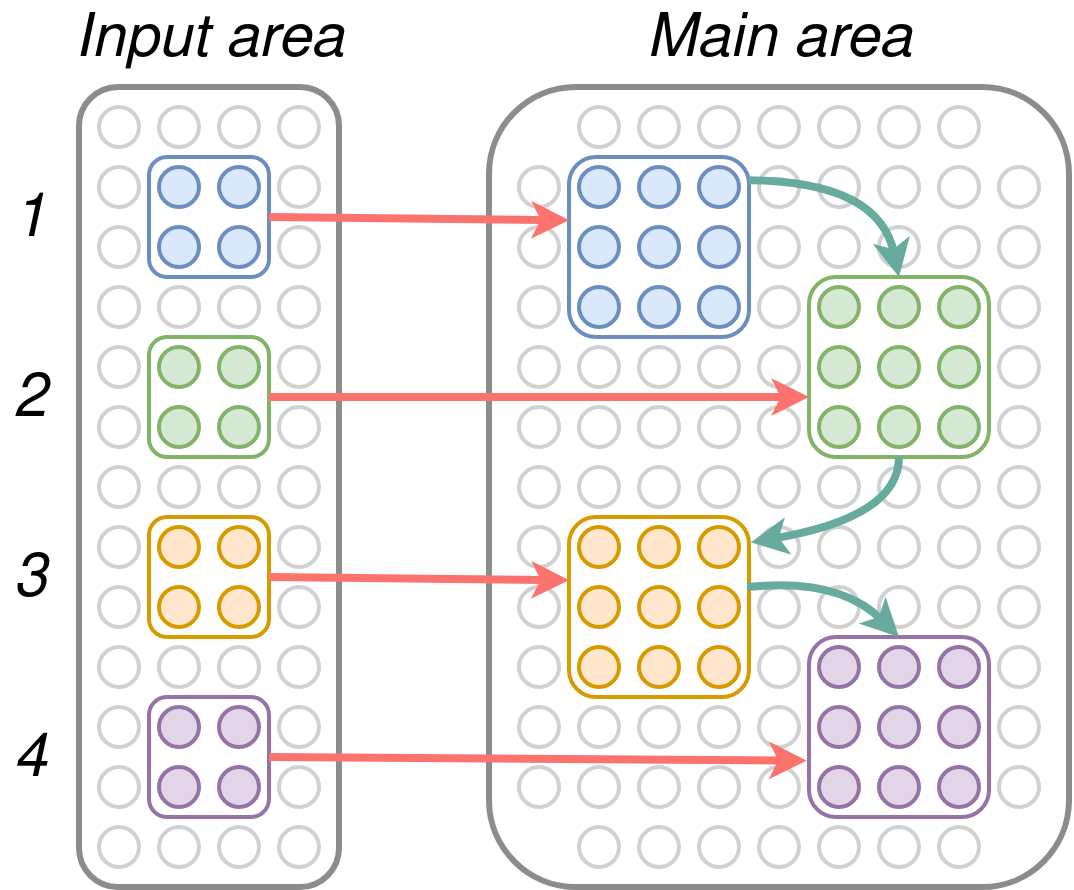

Sequences of assemblies arise quite naturally in NEMO [1]. The simplest setup is much like that for assembly formation, with an input area and a main area. A sequence of stimuli fires in the input area – crucially, a different stimulus fires on each time step. This evokes a sequence of responses in the main area.

As long as the individual stimuli are sufficiently dissimilar from each other, their corresponding responses will be dissimilar from each other as well. And as long as the plasticity is not too strong, this sequence of responses will be exactly the same, each time the stimuli sequence is presented. Thus, after seeing the complete sequence a few times, the responses become memorized, such that seeing only a portion of the input sequence is enough to set off the entire response sequence.

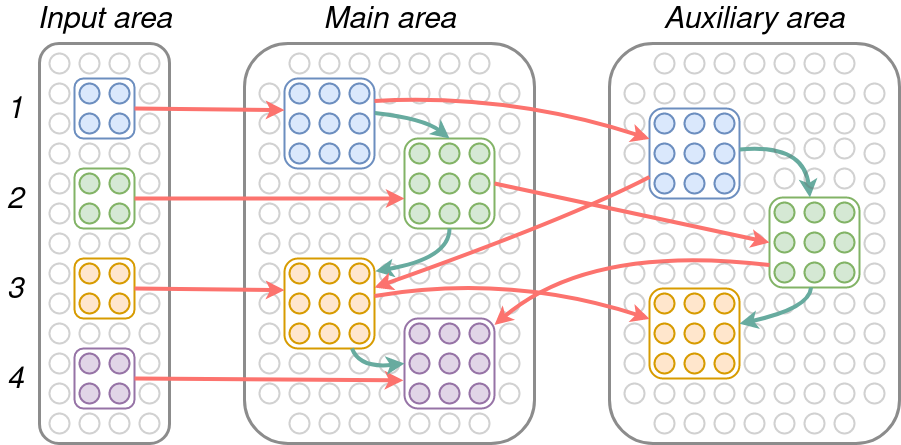

A slight extension of this idea leads to faster memorization, when an additional auxiliary area communicates bidirectionally with the main area. This auxiliary area forms a sequence of its own, which becomes linked (or “scaffolded”) with the main sequence and reinforces it. As a result, fewer presentations of the input sequence are required to achieve memorization.

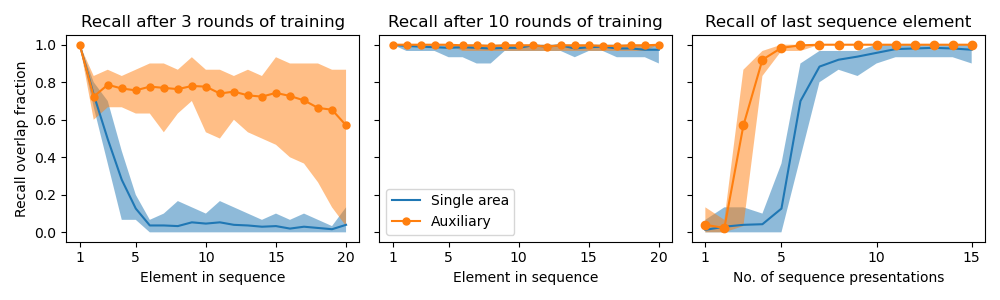

The speedup this gives can be observed experimentally, where we train both simple and scaffold sequence models to memorize a length 20 sequence, and after each presentation of the sequence we test to see how well the last item in the memorized sequence is recalled, when only the first item in the input sequence is presented. The plots are below.

The fact that pulling in additional areas boosts memorization is interesting, as it may be related to the common observation that it is easy to memorize paired sequences together – for instance, the alphabet along with a tune.

Simulating automata

Of course, memorization is merely the simplest operation that can be performed on an input sequence. There are various more sophisticated ways to process sequences – and some of them seem to be at the very heart of cognition. Here, we discuss a natural implementation of a finite-state machine (FSM) in NEMO, a limited but nonetheless powerful automaton that captures the computations which can be performed with very little memory.

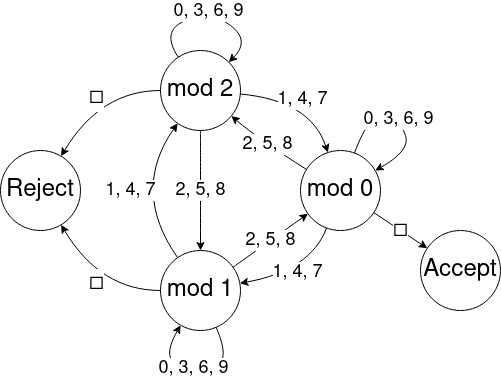

A FSM is an automaton that is always in one of its finite states. It processes sequences of symbols by moving between states, according to a rule (its transition function) which depends on its current state and the current symbol it is reading. Below is a FSM which “recognizes” sequences which read out the digits of a number which is divisible by 3:

It does this by using its state to keep track of the remainder of the sum of the digits it’s seen so far; at the end of the string, if the remainder is zero, it accepts (using the grade school trick for identifying multiples of three) and rejects otherwise.

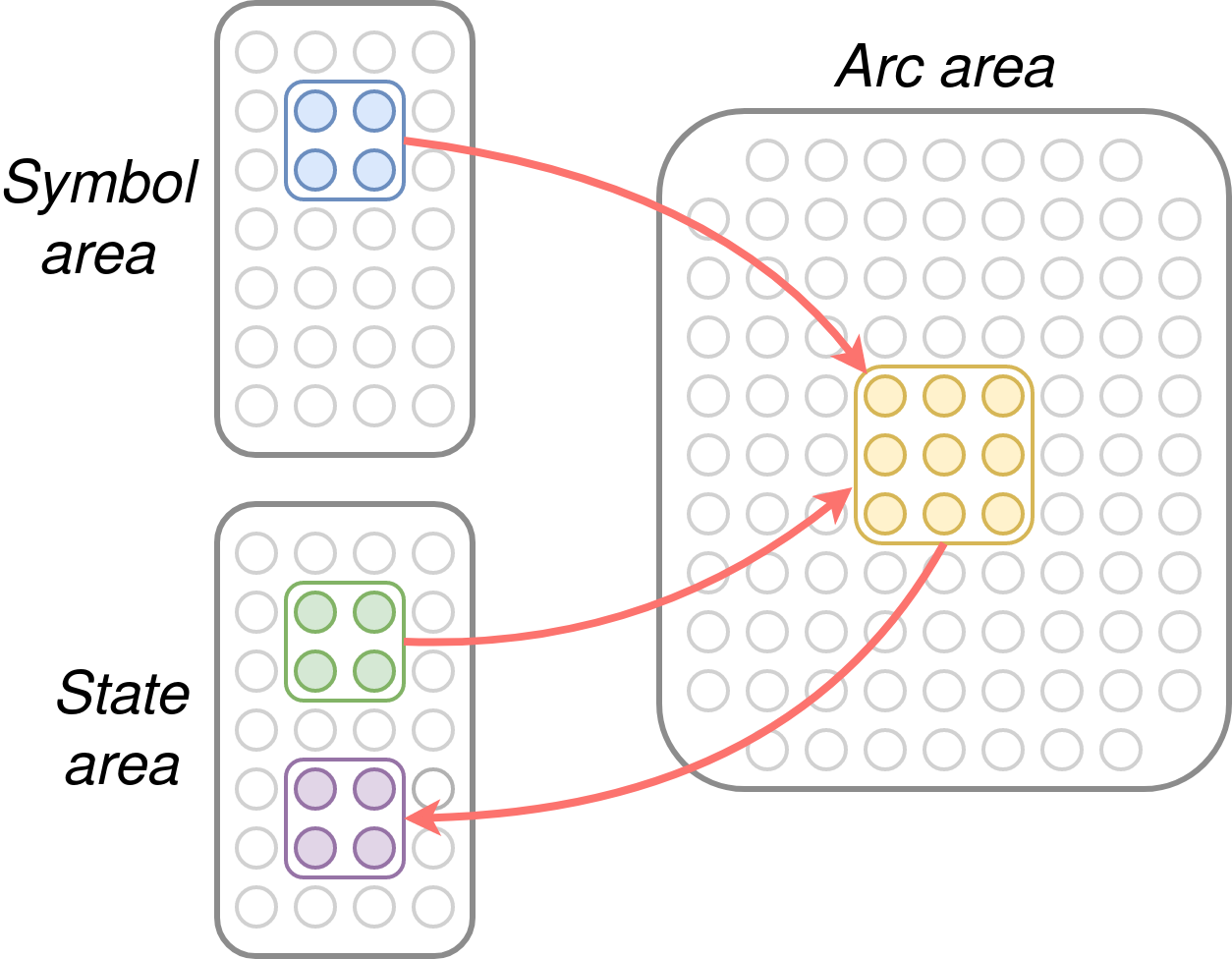

The implementation of a FSM in NEMO involves three areas: a symbol area, a state area, and an arc/transition area. The symbol and state areas both stimulate the arc area, while the arc area stimulates the state area. The symbol area contains an assembly for each symbol, which fires when that symbol is presented, while the state area contains an assembly for each state. The arc area contains an assembly for each pair of a symbol and a state.

Each symbol/state pair is linked to the corresponding arc assembly. That arc assembly in turn is linked to the correct next state under the FSM’s transition function. The result is that when a given symbol/state pair fires together, the correct “next state” assembly fires 2 timesteps later. So, if the sequence of input symbol assemblies is made to fire in the symbol area every other timestep, the process repeats and the FSM gets simulated. Here’s an animation of this deceptively complex process for the FSM above:

Moreover, this structure can easily be trained, simply by firing the correct symbol and state assemblies in sequence, with a timestep in between. This causes the pair assemblies to form in the arc areas and strengthens the synapses from them to their correct next state assemblies. In this way the model could also provide output with each transition (this type of automaton is called a finite-state transducer), by additionally linking output symbol assemblies to the appropriate arc assemblies.

General computation

For computer scientists, an important question about any model of computation is whether it is Turing complete. This is the class of automata that is generally considered to capture everything in the world – from laptops to brains – that we might think of as computation. To be Turing complete, it is sufficient that a model is capable of simulating a Turing machine, which is essentially nothing more than a finite state transducer augmented with an arbitrarily long tape of memory, which it is able to move around on and read and write from, one memory cell at a time.

From the above, NEMO can simulate a finite-state transducer. If its environment implements the necessary tape (for instance within the brain’s specialized memory systems, or in the external world, which it might interact with using motor commands) then this is all that is required. This is reasonable since the Turing machine was originally meant to capture the computational power of a human with a pencil and paper – not a human alone, since our ability to remember arbitrary strings of symbols is rather weak. However, for completeness, there is also an implementation of a Turing machine’s tape in NEMO. This model is highly complex and requires detailed setup and coordination, and is not intended as a serious hypothesis about how cognition is implemented in the brain.

References: