Flipping a Coin with Assemblies

The brain has access to finite information and finite computation, and thus it is limited in its ability to model the world. A natural way to account for the uncertainty this creates is probabilistically – that is, to develop probabilistic models of portions of one’s environment, and use these models to make decisions. Indeed, this approach has been tremendously successful in very difficult domains such as language, where the entire problem of conversational agency can be reduced to a good probability distribution over the next token conditioned on previous ones.

The assembly coinflip

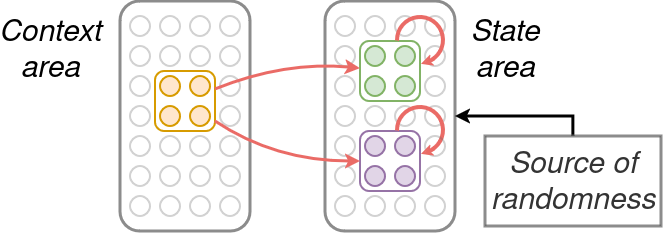

The simplest version of this problem has two outcomes. The problem is to realize a probability distribution over these outcomes that may depend on a contextual variable. In NEMO this may be implemented using a “context” area which stimulates a “state” area, where the context area contains an assembly for each possible value of the context variable and the state area contains an assembly for each outcome (here, 2) [1]. Additionally, the state area has access to a source of randomness, which adds a small independent and identically distributed perturbation to the activation of each neuron in the state area.

The probability distribution in this case turns out to be determined by the weights from the context assembly to the outcome assemblies. For a fair coin toss, the two outcome assemblies have the same weight with the context assembly. When the context assembly fires, exactly k neurons fire in the state area, like usual – but the random perturbation ensures that the two outcomes have roughly equal probability of having a slight advantage in numbers in this first cap. In subsequent caps, strong recurrent connectivity within the outcome assemblies amplifies this initial advantage so that the initial leader quickly comes to fire entirely. More generally, the probability that one outcome obtains the initial advantage depends on the weights in a nice way: it is approximately the softmax of the weights with scaling determined by the parameters of NEMO.

Beyond just implementing a coin flip, to construct models of its environment the brain needs to learn the probabilities of its model from observations. In other words, the probability of a outcome occurring in a particular context should match the empirical frequency with which that outcome/context pair was observed. Since the probability distribution based on the weights is a softmax, a particular yet simple Hebbian plasticity rule can “invert” the softmax, so that the probability and empirical frequency approximately coincide.

Notably, in experiment this setup works with a large number of outcomes, but in theory it has only been shown to hold for two.

More complex models

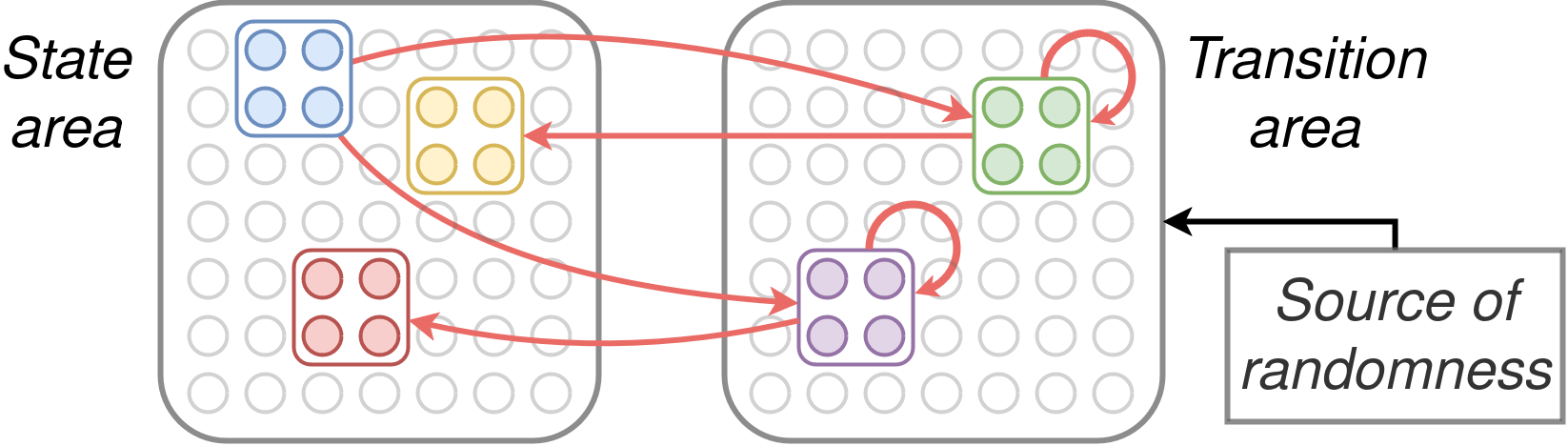

The basic assembly coinflip is a useful gadget to use in the construction of more complex models. A simple yet surprisingly powerful model is the Markov chain, which generates sequences of states (or observations). A sequence can be sampled from a (stationary) Markov chain by repeatedly applying and sampling from its transition function, which maps a current state to a probability distribution over the next state. This straightforwardly reduces to the coinflipping case – context corresponds to the current state, and outcomes correspond to the next state.

To implement a Markov chain in NEMO we need two areas, a current state area and a next state area, connected bidirectionally and each containing an assembly for every state. The next state assemblies link directly back to their current state copies, while weights from the current state assemblies to the next state assemblies encode the transition function of the Markov chain. We assume that the inhibition schedule briefly allows the current state area to fire, then inhibits it while allowing the next state area to fire for several timesteps (which allows an outcome to be chosen), and then repeats indefinitely.

To sample, one simply sets a current state assembly to fire and then allows the NEMO dynamics to unfold. This model too can be learned from observations, by simply firing the appropriate sequence of correct and next state assemblies.

References: